Whether it’s for the Big C or the Fire Trails, the Berkeley Hills find their way onto every Berkeley student’s list of token destinations.

However, when we commit ourselves to trekking those ridiculous slopes, we often only look to the sky to catch the west coast sunsets, the stars on a clear night, the sprawling bay view lit up in the darkness. Yet we sparingly turn our attention downwards (except to catch a clumsy misstep). This is unfortunate, as we are walking atop an amazing record of geologic history.

As a child I’ve always loved rocks, I was one of those kids, the kind that filled entire dresser drawers with collected stones, and later played with them instead of dolls. Even so, until I took Earth and Planetary Science 50 here at Berkeley I had no idea of the real-world stories these rocks could tell.

Back in the Berkeley hills, you might walk past a wall of vertically-oriented grey and off-white rock layers.

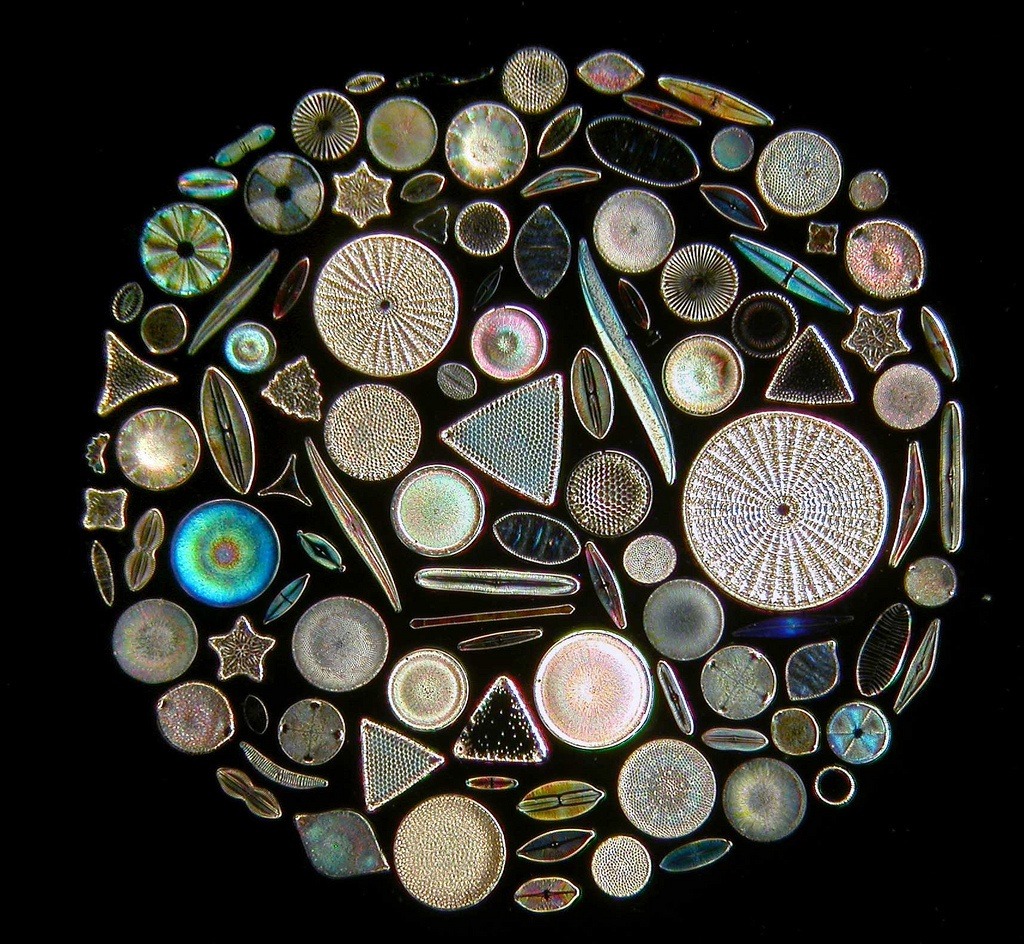

What you might not know, though, is that the grey layers are Shales, fine-grained sedimentary rock created by ancient turbidity currents, dramatic undersea landslides. The white could be Chert, the accumulated result of tiny diatoms which died and sank to the seabed.

When you look even closer at chert, you might notice thin bands. Just like with trees, each band marks one season of deposition. From the color and size, you could even determine how much food the diatoms had access to in a summer.

And we can’t forget the vertical tilt! The Law of Original Horizontality states that sediment layers are initially deposited horizontally. To have vertical sedimentary layers there must have been a massive tectonic event that uplifted the beds.

Geologists call the angle the beds tilt into a horizontal plane “dip” and the direction of the bed on that plane “strike”. They can use these measurements to examine the uplifting mechanisms that caused the tilt. Try to allow the earth you tread to serve as a reminder that rocks are not simply stagnant scenery, but rather the relics of dynamic stories in natural history.

You can also bring this philosophy closer to home. Take the granite counter in your kitchen. Sure it is durable, withstanding years of chopping and slicing in dinner prep. This can be attributed to granite’s Moh’s hardness of around 6-7. A steel knife rings in at 5. The Mohs Scale is used to determine the relative hardness of a mineral compared to another mineral.

Granite of course is not one mineral, but many. It is an intrusive igneous rock formed deep in the earth by felsic minerals (predominantly feldspars, micas, and quartz). Even these minerals tell a story.  Geologists use Bowen’s Reaction Series to depict the orderly sequence of how minerals crystallize in igneous rocks. The feldspars in your counter (the pink and white specs) will even have different potassium and sodium concentrations, depending on their temperatures during early crystallization. Who would have guessed your kitchen could be a mineralogist’s dream?

Geologists use Bowen’s Reaction Series to depict the orderly sequence of how minerals crystallize in igneous rocks. The feldspars in your counter (the pink and white specs) will even have different potassium and sodium concentrations, depending on their temperatures during early crystallization. Who would have guessed your kitchen could be a mineralogist’s dream?

Next time you walk along Strawberry Creek, pick up a rock and look, really look at it. Maybe it has tiny red crystals interspersed in a dark, fine-grained matrix. If so, it could be a porphyritic basalt with garnet phenocrysts, which would tell us that the garnets formed deep underground before being extruded.

Maybe it has a slightly blue-ish tint. This could be a blueschist fragment, a low grade metamorphic rock formed at low temperatures but high pressures. These rather rare conditions are found exclusively in subduction zones, places where one denser plate slides underneath a lighter one. The blue, a scarce hue in the rock world, comes from the mineral glaucophane. If you wish to see a large-scale blue rock formation, Ring Mountain in Marin County is one of the best places to spot blue schist and makes a very nice hike.

Rocks are such a constant feature in our daily scenery that sadly, they easily fade into the background. However, they truly deserve our attention, for they are timeless, they are mobile, they take us back in time to bygone earths, they teach us of the gargantuan forces that make up our geodynamo. I accept that not everyone is a natural geophile, and that the geologic time scale of millions and billions of years can be harder to wrap your mind around compared to the smaller time scale of biology. All the same, I urge you all to occasionally watch where you step, and let the ground beneath your feet remind you of the amazing and enduring mechanisms that make up this rocky planet we happen to tread upon.

3 responses to “Watch Where You Step: A Geophile’s Manifesto”

Great article, we enjoyed reading it. Brian & Janine

Thank you, I really appreciate it!

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you have put

in writing this site. I’m hoping to see the same high-grade content from

you later on as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities has motivated me to get my own, personal website now 😉